Revolutions Of 1848 In The Austrian Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a set of revolutions that took place in the

Conflicts between

Conflicts between

After news broke of the February victories in Paris, uprisings occurred throughout Europe, including in

After news broke of the February victories in Paris, uprisings occurred throughout Europe, including in  However, liberal ministers were unable to establish central authority. Provisional governments in

However, liberal ministers were unable to establish central authority. Provisional governments in

By early summer, conservative regimes had been overthrown, new freedoms (including freedom of the press and freedom of association) had been introduced, and multiple nationalist claims had been exerted. New parliaments quickly held elections with broad franchise to create constituent assemblies, which would write new constitutions. The elections that were held produced unexpected results. The new voters, naïve and confused by their new political power, typically elected conservative or moderately liberal representatives. The radicals, the ones who supported the broadest franchise, lost under the system they advocated because they were not the locally influential and affluent men. The mixed results led to confrontations similar to the "June Days" uprising in Paris. Additionally, these constituent assemblies were charged with the impossible task of managing both the needs of the people of the state and determining what that state physically is at the same time. The Austrian Constituent Assembly was divided into a Czech faction, a German faction, and a Polish faction, and within each faction was the political left-right spectrum. Outside the Assembly, petitions, newspapers, mass demonstrations, and political clubs put pressure on their new governments and often expressed violently many of the debates that were occurring within the assembly itself.

The Czechs held a Pan-Slavic congress in

By early summer, conservative regimes had been overthrown, new freedoms (including freedom of the press and freedom of association) had been introduced, and multiple nationalist claims had been exerted. New parliaments quickly held elections with broad franchise to create constituent assemblies, which would write new constitutions. The elections that were held produced unexpected results. The new voters, naïve and confused by their new political power, typically elected conservative or moderately liberal representatives. The radicals, the ones who supported the broadest franchise, lost under the system they advocated because they were not the locally influential and affluent men. The mixed results led to confrontations similar to the "June Days" uprising in Paris. Additionally, these constituent assemblies were charged with the impossible task of managing both the needs of the people of the state and determining what that state physically is at the same time. The Austrian Constituent Assembly was divided into a Czech faction, a German faction, and a Polish faction, and within each faction was the political left-right spectrum. Outside the Assembly, petitions, newspapers, mass demonstrations, and political clubs put pressure on their new governments and often expressed violently many of the debates that were occurring within the assembly itself.

The Czechs held a Pan-Slavic congress in

In 1848, news of the outbreak of revolution in Paris arrived as a new national cabinet took power under Kossuth, and the Diet approved a sweeping reform package, referred to as the "

In 1848, news of the outbreak of revolution in Paris arrived as a new national cabinet took power under Kossuth, and the Diet approved a sweeping reform package, referred to as the " Aware that they were on the path to civil war in mid-1848, the Hungarian government ministers attempted to gain Habsburg support against Jelačić by offering to send troops to northern Italy. Additionally, they attempted to come to terms with Jelačić himself, but he insisted on the recentralization of Habsburg authority as a pre-condition to any talks. By the end of August, the imperial government in

Aware that they were on the path to civil war in mid-1848, the Hungarian government ministers attempted to gain Habsburg support against Jelačić by offering to send troops to northern Italy. Additionally, they attempted to come to terms with Jelačić himself, but he insisted on the recentralization of Habsburg authority as a pre-condition to any talks. By the end of August, the imperial government in

Slovak Uprising was an uprising of

Slovak Uprising was an uprising of

Digitized version

{{DEFAULTSORT:Revolutions Of 1848 Austrian Empire . .Austrian Empire 19th century in Bohemia 1840s in Croatia 1848 in Hungary 1848 in Romania 19th century in Slovakia 19th-century revolutions Conflicts in 1849 Hungarian Revolution of 1848 Rebellions against the Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

from March 1848 to November 1849. Much of the revolutionary activity had a nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

character: the Empire, ruled from Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, included ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

, Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

, Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovene as their n ...

, Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

, Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, c ...

, Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

, Ruthenians

Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sourc ...

(Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

), Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Culture of Romania, Romanian culture and Cultural heritage, ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they l ...

, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, G ...

, Venetians and Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

; all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to either achieve autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

, independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, or even hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

Besides these nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

, liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and even socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

currents resisted the Empire's longstanding conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

.

Preamble

The events of 1848 were the product of mounting social and political tensions after theCongress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

of 1815. During the "pre-March" period, the already conservative Austrian Empire moved further away from ideas of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, restricted freedom of the press, limited many university activities, and banned fraternities.

Social and political conflict

Conflicts between

Conflicts between debtor

A debtor or debitor is a legal entity (legal person) that owes a debt to another entity. The entity may be an individual, a firm, a government, a company or other legal person. The counterparty is called a creditor. When the counterpart of this ...

s and creditor

A creditor or lender is a party (e.g., person, organization, company, or government) that has a claim on the services of a second party. It is a person or institution to whom money is owed. The first party, in general, has provided some property ...

s in agricultural

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating Plant, plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of Sedentism, sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of Domestication, domesticated species created food ...

production as well as over land use rights in parts of Hungary led to conflicts that occasionally erupted into violence. Conflict over organized religion was pervasive in pre-1848 Europe. Tension came both from within Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and between members of different confessions. These conflicts were often mixed with conflict with the state. Important for the revolutionaries were state conflicts including the armed forces and collection of taxes. As 1848 approached, the revolutions the Empire crushed to maintain longstanding conservative minister Klemens Wenzel von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

's Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying f ...

left the empire nearly bankrupt and in continual need of soldiers. Draft commissions led to brawls between soldiers and civilians. All of this further agitated the peasantry, who resented their remaining feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

obligations.

Despite lack of freedom of the press and association, there was a flourishing liberal German culture among students and those educated either in Josephine schools or German universities. They published pamphlets and newspapers discussing education and language; the need for basic liberal reforms was assumed. These middle class liberals largely understood and accepted that forced labor is not efficient, and that the Empire should adopt a wage labor system. The question was how to institute such reforms.

Notable liberal clubs of the time in Vienna included the Legal-Political Reading Club (established 1842) and Concordia Society (1840). They, like the Lower Austrian Manufacturers' Association (1840) were part of a culture that criticized Metternich's government from the city's coffeehouse

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-ca ...

s, salons, and even stages, but prior to 1848 their demands had not even extended to constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

or freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

, let alone republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

. They had merely advocated relaxed censorship, freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

, economic freedoms, and, above all, a more competent administration. They were opposed to outright popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

and the universal franchise

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

.

More to the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

was a radicalized, impoverished intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

. Educational opportunities in 1840s Austria had far outstripped employment opportunities for the educated.

Direct cause of the outbreak of violence

In 1845,potato blight

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by ''Alternaria solani'', is also often called "po ...

arrived to Belgium from North America, thus starting the Hungry Forties

The European Potato Failure was a food crisis caused by potato blight that struck Northern and Western Europe in the mid-1840s. The time is also known as the Hungry Forties. While the crisis produced excess mortality and suffering across the aff ...

. As the disease quickly spreaded through Europe, the major calorie source for the poorer population failed and food prices soared. In 1846 there had been an uprising of Polish nobility in Austrian Galicia, which was only countered when peasants, in turn, rose up against the nobles. The economic crisis of 1845–47 was marked by recession and food shortages throughout the continent. At the end of February 1848, demonstrations broke out in Paris. Louis Philippe of France

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary War ...

abdicated the throne, prompting similar revolts throughout the continent.

Revolution in the Austrian lands

An early victory leads to tension

After news broke of the February victories in Paris, uprisings occurred throughout Europe, including in

After news broke of the February victories in Paris, uprisings occurred throughout Europe, including in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, where the Diet (parliament) of Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt P ...

in March demanded the resignation of Prince Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

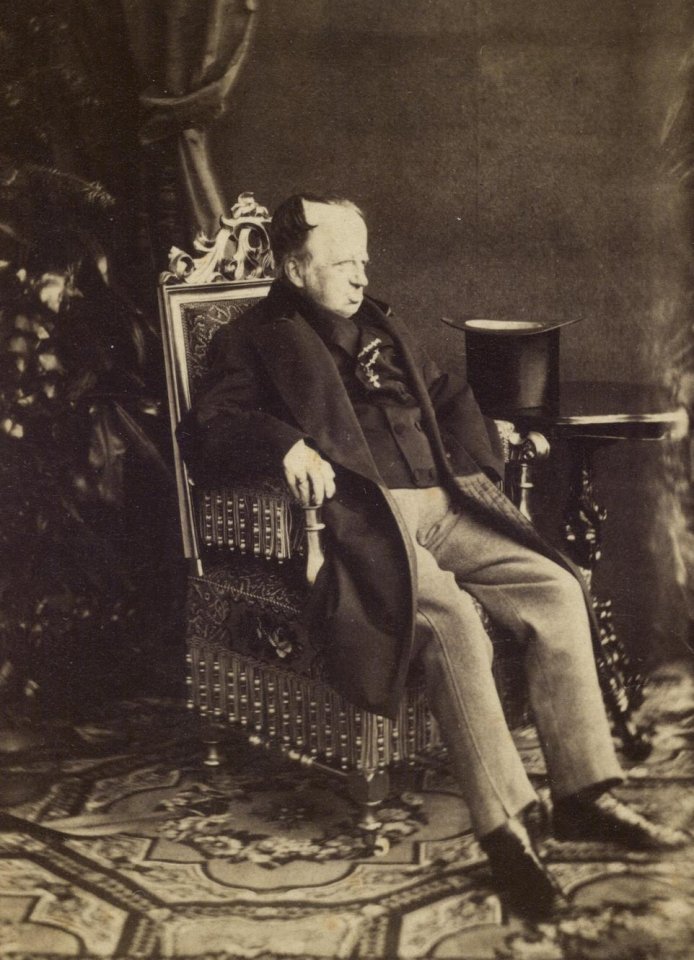

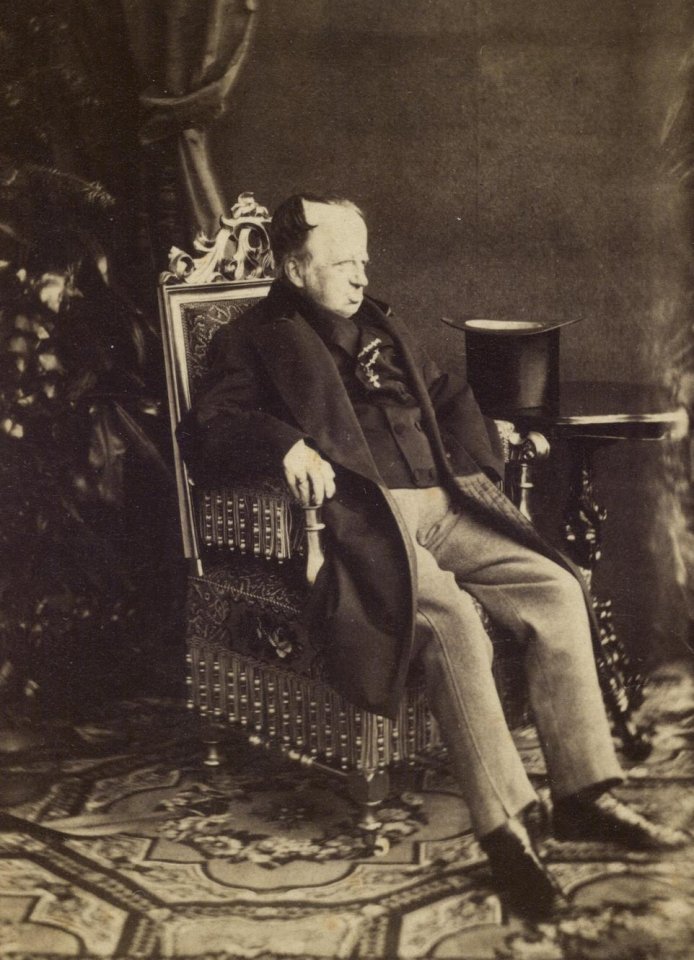

, the conservative State Chancellor and Foreign Minister. With no forces rallying to Metternich's defense, nor word from Ferdinand I of Austria

en, Ferdinand Charles Leopold Joseph Francis Marcelin

, image = Kaiser Ferdinand I.jpg

, caption = Portrait by Eduard Edlinger (1843)

, succession = Emperor of AustriaKing of Hungary

, moretext = ( more...)

, cor-type = ...

to the contrary, he resigned on 13 March. Metternich fled to London, and Ferdinand appointed new, nominally liberal, ministers. By November, the Austrian Empire saw several short-lived liberal governments under five successive Ministers-President of Austria

A minister-president or minister president is the head of government in a number of European countries or subnational governments with a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government where they preside over the council of ministers. It ...

: Count Kolowrat (17 March–4 April), Count Ficquelmont (4 April–3 May), Baron Pillersdorf (3 May–8 July), Baron Doblhoff-Dier (8 July–18 July) and Baron Wessenberg (19 July–20 November).

The established order collapsed rapidly because of the weakness of the Austrian armies. Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky was unable to keep his soldiers fighting Venetian and Milanese insurgents in Lombardy-Venetia, and had to, instead, order the remaining troops to evacuate.

Social and political conflict as well as inter and intra confessional hostility momentarily subsided as much of the continent rejoiced in the liberal victories. Mass political organizations and public participation in government became widespread.

However, liberal ministers were unable to establish central authority. Provisional governments in

However, liberal ministers were unable to establish central authority. Provisional governments in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

quickly expressed a desire to be part of an Italian confederacy of states; but for the Venetian government this lasted only five days, after the 1848 armistice between Austria and Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. A new Hungarian government in Pest announced its intentions to break away from the Empire and elect Ferdinand its King, and a Polish National Committee announced the same for the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

.

Social and political tensions after the "Springtime of Peoples"

The victory of the party of movement was looked at as an opportunity for lower classes to renew old conflicts with greater anger and energy. Several tax boycotts and attempted murders of tax collectors occurred inVienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. Assaults against soldiers were common, including against Radetzky's troops retreating from Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. The archbishop of Vienna was forced to flee, and in Graz, the convent of the Jesuits was destroyed.

The demands of nationalism and its contradictions became apparent as new national governments began declaring power and unity. Charles Albert of Sardinia

Charles Albert (; 2 October 1798 – 28 July 1849) was the King of Sardinia from 27 April 1831 until 23 March 1849. His name is bound up with the first Italian constitution, the Albertine Statute, and with the First Italian War of Independence ...

, King of Piedmont-Savoy, initiated a nationalist war on March 23 in the Austrian held northern Italian provinces that would consume the attention of the entire peninsula. The German nationalist movement faced the question of whether or not Austria should be included in the united German state, a quandary that divided the Frankfurt National Assembly

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

. The liberal ministers in Vienna were willing to allow elections for the German National Assembly in some of the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

lands, but it was undetermined which Habsburg territories would participate. Hungary and Galicia were clearly not German; German nationalists (who dominated the Bohemian Diet) felt the old crown lands rightfully belonged to a united German state, despite the fact that the majority of the people of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

spoke Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

— a Slavic language

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto ...

. Czech nationalists viewed the language as far more significant, calling for a boycott of the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

elections in Bohemia, Moravia, and neighboring Austrian Silesia

Austrian Silesia, (historically also ''Oesterreichisch-Schlesien, Oesterreichisch Schlesien, österreichisch Schlesien''); cs, Rakouské Slezsko; pl, Śląsk Austriacki officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, (historically ''Herzogth ...

(also partly Czech-speaking). Tensions in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

between German and Czech nationalists grew quickly between April and May. After the abolition of serfdom on April 17, Supreme Ruthenian Council

Supreme Ruthenian Council ( uk, Головна Руська Рада, Holovna Ruska Rada) was the first legal Ruthenian political organization that existed from May 1848 to June 1851.

It was founded on 2 May 1848 in Lemberg (today Lviv), Austri ...

was established in Galicia to promote the unification of ethnic Ukrainian lands of Eastern Galicia, Transcarpathia

Transcarpathia may refer to:

Place

* relative term, designating any region beyond the Carpathians (lat. ''trans-'' / beyond, over), depending on a point of observation

* Romanian Transcarpathia, designation for Romanian regions on the inner or ...

and Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

in one province. Ukrainian language

Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an East Slavic language of the Indo-European language family. It is the native language of about 40 million people and the official state langu ...

department was opened in Lviv University

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

, and the first Ukrainian newspaper ''Zoria Halytska'' started publishing in Lviv on May 15, 1848. On July 1, serfdom was also abolished in Bukovina.

By early summer, conservative regimes had been overthrown, new freedoms (including freedom of the press and freedom of association) had been introduced, and multiple nationalist claims had been exerted. New parliaments quickly held elections with broad franchise to create constituent assemblies, which would write new constitutions. The elections that were held produced unexpected results. The new voters, naïve and confused by their new political power, typically elected conservative or moderately liberal representatives. The radicals, the ones who supported the broadest franchise, lost under the system they advocated because they were not the locally influential and affluent men. The mixed results led to confrontations similar to the "June Days" uprising in Paris. Additionally, these constituent assemblies were charged with the impossible task of managing both the needs of the people of the state and determining what that state physically is at the same time. The Austrian Constituent Assembly was divided into a Czech faction, a German faction, and a Polish faction, and within each faction was the political left-right spectrum. Outside the Assembly, petitions, newspapers, mass demonstrations, and political clubs put pressure on their new governments and often expressed violently many of the debates that were occurring within the assembly itself.

The Czechs held a Pan-Slavic congress in

By early summer, conservative regimes had been overthrown, new freedoms (including freedom of the press and freedom of association) had been introduced, and multiple nationalist claims had been exerted. New parliaments quickly held elections with broad franchise to create constituent assemblies, which would write new constitutions. The elections that were held produced unexpected results. The new voters, naïve and confused by their new political power, typically elected conservative or moderately liberal representatives. The radicals, the ones who supported the broadest franchise, lost under the system they advocated because they were not the locally influential and affluent men. The mixed results led to confrontations similar to the "June Days" uprising in Paris. Additionally, these constituent assemblies were charged with the impossible task of managing both the needs of the people of the state and determining what that state physically is at the same time. The Austrian Constituent Assembly was divided into a Czech faction, a German faction, and a Polish faction, and within each faction was the political left-right spectrum. Outside the Assembly, petitions, newspapers, mass demonstrations, and political clubs put pressure on their new governments and often expressed violently many of the debates that were occurring within the assembly itself.

The Czechs held a Pan-Slavic congress in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

between June 2 and June 12, 1848. It was primarily composed of Austroslavs who wanted greater freedom within the Empire, but their status as peasants and proletarians

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

surrounded by a German middle class doomed their autonomy . They also disliked the prospect of annexation of Bohemia to a German Empire.

Counterrevolution

Insurgents quickly lost in street fighting to King Ferdinand's troops led by General Radetzky, prompting several liberal government ministers to resign in protest. Ferdinand, now restored to power inVienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, appointed conservatives in their places. These actions were a considerable blow to the revolutionaries, and by August most of northern Italy was under Radetzky's control.

In Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, the leaders of both the German and Czech nationalist movements were both constitutional monarchists, loyal to the Habsburg Emperor. Only a few days after the Emperor reconquered northern Italy, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*''Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interlu ...

took provocative measures in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

to prompt street fighting

Street fighting is hand-to-hand combat in public places, between individuals or groups of people. The venue is usually a public place (e.g. a street) and the fight sometimes results in serious injury or occasionally even death. Some street fi ...

. Once the barricades went up, he led Habsburg troops to crush the insurgents. After having taken back the city, he imposed martial law, ordered the Prague National Committee dissolved, and sent delegates to the "Pan-Slavic" Congress home. These events were applauded by German nationalists, who failed to understand that the Habsburg military would crush their own national movement as well.

Attention then turned to Hungary. War in Hungary again threatened imperial rule and prompted Emperor Ferdinand and his court to once more flee Vienna. Viennese radicals welcomed the arrival of Hungarian troops as the only force able to stand up against the court and ministry. The radicals took control of the city for only a short period of time. Windisch-Grätz led soldiers from Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

to quickly defeat the insurgents. Windisch-Grätz restored imperial authority to the city. The reconquering of Vienna was seen as a defeat over German nationalism. At this point, Ferdinand I named the noble Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg

Felix Ludwig Johann Friedrich, Prince of Schwarzenberg (german: Felix Ludwig Johann Friedrich Prinz zu Schwarzenberg; cs, Felix Ludvík Jan Bedřich princ ze Schwarzenbergu; 2 October 1800 – 5 April 1852) was a Bohemian nobleman and an Au ...

head of government. Schwarzenberg, a consummate statesman, persuaded the feeble-minded Ferdinand to abdicate the throne to his 18-year-old nephew, Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

. Parliamentarians continued to debate, but had no authority on state policy.

Both the Czech and Italian revolutions were defeated by the Habsburgs. Prague was the first victory of counter-revolution in the Austrian Empire.

Lombardy-Venetia was quickly brought back under Austrian rule in the mainland, even because popular support for the revolution vanished: revolutionary ideals were often limited to part of middle and upper classes, which failed both to gain "hearts and minds" of lower classes and to convince the population about Italian nationalism. Most part of lower classes indeed were quite indifferent, and actually most part of Lombard and Venetian troops remained loyal. The only widespread support to the revolution was in the cities of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, with the Republic of San Marco lasting under siege until 28th of August, 1849.

Revolution in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Hungarian Diet was reconvened in 1825 to handle financial needs. A liberal party emerged in the Diet. The party focused on providing for the peasantry in mostly symbolic ways because of their inability to understand the needs of the laborers.Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, poli ...

emerged as the leader of the lower gentry in the Diet.

In 1848, news of the outbreak of revolution in Paris arrived as a new national cabinet took power under Kossuth, and the Diet approved a sweeping reform package, referred to as the "

In 1848, news of the outbreak of revolution in Paris arrived as a new national cabinet took power under Kossuth, and the Diet approved a sweeping reform package, referred to as the "April laws

The April Laws, also called March Laws, were a collection of laws legislated by Lajos Kossuth with the aim of modernizing the Kingdom of Hungary into a Parliamentary system, parliamentary democracy, nation state. The imperative program include ...

" (also "March laws"), that changed almost every aspect of Hungary's economic, social, and political life: (The April laws based on the 12 points:

*Freedom of the Press (The abolition of censure and the censor's offices)

*Accountable ministries in Buda and Pest (Instead of the simple royal appointment of ministers, all ministers and the government must be elected and dismissed by the parliament)

*An annual parliamentary session in Pest. (instead of the rare ad-hoc sessions which was convoked by the king)

*Civil and religious equality before the law. (The abolition of separate laws for the common people and nobility, the abolition of the legal privileges of nobility. Full religious liberty instead of moderated tolerance: the abolition of (Catholic) state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

)

*National Guard. (The forming of their own Hungarian national guard, it worked like a police force to keep the law and order during the transition of the system, thus preserving the morality of the revolution)

*Joint share of tax burdens. (abolition of the tax exemption of the nobility, the abolition of customs and tariff exemption of the nobility)

*The abolition of socage. (abolition of Feudalism and abolition of the serfdom of peasantry and their bondservices)

*Juries and representation on an equal basis. (The common people can be elected as juries at the legal courts, all people can be officials even on the highest levels of the public administration and judicature, if they have the prescribed education)

*National Bank.

*The army to swear to support the constitution, our soldiers should not be sent to abroad, and foreign soldiers should leave our country.

*The freeing of political prisoners.

*Union with Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

These demands were not easy for the imperial court to accept, however, its weak position provided little choice. One of the first tasks of the Diet was abolishing serfdom, which was announced on March 18, 1848.

The Hungarian government set limits on the political activity of both the Croatian and Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

*** Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

** Romanian cuisine, tradition ...

national movements. Croats and Romanians had their own desires for self-rule and saw no benefit in replacing one central government for another. Armed clashes between the Hungarians and the Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic, G ...

, Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Culture of Romania, Romanian culture and Cultural heritage, ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they l ...

, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

, along one border and Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

on the other ensued. In some cases, this was a continuation and an escalation of previous tensions, such as the 1845 July victims

The July victims ( hr, Srpanjske žrtve) were members of the Croatian People's Party who fell victim to a crackdown by the Austrian Imperial Army on July 29, 1845.

In 1845, there were local elections for the government of Zagreb County, the count ...

in Croatia.

The Habsburg Kingdom of Croatia

The Kingdom of Croatia ( hr, Kraljevina Hrvatska; la, Regnum Croatiae; hu, Horvát Királyság, german: Königreich Kroatien) was part of the lands of the Habsburg monarchy from 1527, following the Election in Cetin, and the Austrian Empire from ...

and the Kingdom of Slavonia

The Kingdom of Slavonia ( hr, Kraljevina Slavonija, la, Regnum Sclavoniae, hu, Szlavón Királyság, german: Königreich Slawonien, sr-Cyrl, Краљевина Славонија) was a kingdom of the Habsburg monarchy and the Austrian Empi ...

severed relations with the new Hungarian government in Pest and devoted itself to the imperial cause. Conservative Josip Jelačić, who was appointed the new ban of Croatia-Slavonia in March by the imperial court, was removed from his position by the constitutional monarchist Hungarian government. He refused to give up his authority in the name of the monarch. Thus, there were two governments in Hungary issuing contradictory orders in the name of Ferdinand von Habsburg.

Aware that they were on the path to civil war in mid-1848, the Hungarian government ministers attempted to gain Habsburg support against Jelačić by offering to send troops to northern Italy. Additionally, they attempted to come to terms with Jelačić himself, but he insisted on the recentralization of Habsburg authority as a pre-condition to any talks. By the end of August, the imperial government in

Aware that they were on the path to civil war in mid-1848, the Hungarian government ministers attempted to gain Habsburg support against Jelačić by offering to send troops to northern Italy. Additionally, they attempted to come to terms with Jelačić himself, but he insisted on the recentralization of Habsburg authority as a pre-condition to any talks. By the end of August, the imperial government in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

officially ordered the Hungarian government in Pest to end plans for a Hungarian army. Jelačić then took military action against the Hungarian government without any official order.

The national assembly of the Serbs in Austrian Empire was held between 1 and 3 May 1848 in Sremski Karlovci

Sremski Karlovci ( sr-cyrl, Сремски Карловци, ; hu, Karlóca; tr, Karlofça) is a town and municipality located in the South Bačka District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. It is situated on the banks of the Danu ...

, during which the Serbs proclaimed autonomous Habsburg crownland of Serbian Vojvodina

The Serbian Vojvodina ( sr, Српска Војводина / ) was a short-lived self-proclaimed Serbs, Serb autonomous province within the Austrian Empire during the Revolutions of 1848, which existed until 1849 when it was transformed into the ...

. The war started, leading to clashes as such in Srbobran

Srbobran ( sr, Србобран, ; hu, Szenttamás) is a town and municipality located in the South Bačka District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The town is located on the north bank of the Danube-Tisa-Danube canal. The town ...

, where on July 14, 1848, the first siege of the town by Hungarian forces began under Baron Fülöp Berchtold. The army was forced to retreat due to a strong Serbian defense. With war raging on three fronts (against Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Culture of Romania, Romanian culture and Cultural heritage, ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they l ...

and Serbs in Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of T ...

and Bačka, and Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Culture of Romania, Romanian culture and Cultural heritage, ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they l ...

in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

), Hungarian radicals in Pest saw this as an opportunity. Parliament made concessions to the radicals in September rather than let the events erupt into violent confrontations. Shortly thereafter, the final break between Vienna and Pest occurred when Field Marshal Count Franz Philipp von Lamberg

Count Franz Philipp von Lamberg ( hu, Lamberg Ferenc Fülöp ''gróf'', 30 November 179128 September 1848) was an Austrian soldier and statesman, who held the military rank of field marshal (German: ''Feldmarschallleutnant''). He had a short but i ...

was given control of all armies in Hungary (including Jelačić's). In response to Lamberg being attacked on arrival in Hungary a few days later, the imperial court ordered the Hungarian parliament and government dissolved. Jelačić was appointed to take Lamberg's place. War between Austria and Hungary had officially begun.

The war led to the October Crisis

The October Crisis (french: Crise d'Octobre) refers to a chain of events that started in October 1970 when members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the provincial Labour Minister Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James C ...

in Vienna, when insurgents attacked a garrison on its way to Hungary to support Croatian forces under Jelačić.

After Vienna was recaptured by imperial forces, General Windischgrätz and 70,000 troops were sent to Hungary to crush the Hungarian revolution and as they advanced the Hungarian government evacuated Pest. However the Austrian army had to retreat after heavy defeats in the Spring Campaign of the Hungarian Army from March to May 1849. Instead of pursuing the Austrian army, the Hungarians stopped to retake the Fort of Buda and prepared defenses. In June 1849 Russian and Austrian troops entered Hungary heavily outnumbering the Hungarian army. Kossuth abdicated on August 11, 1849 in favour of Artúr Görgey, who he thought was the only general who was capable of saving the nation.

However, in May 1849, Czar Nicholas I pledged to redouble his efforts against the Hungarian Government. He and Emperor Franz Joseph started to regather and rearm an army to be commanded by Anton Vogl, the Austrian lieutenant-field-marshal. The Czar was also preparing to send 30,000 Russian soldiers back over the Eastern Carpathian Mountains from Poland.

On August 13, after several bitter defeats in a hopeless situation Görgey, signed a surrender at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed the army over to the Austrians.

Western Slovak Uprising

Slovak Uprising was an uprising of

Slovak Uprising was an uprising of Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

against Magyar (i.e. ethnic Hungarian) domination in the Western parts of Upper Hungary

Upper Hungary is the usual English translation of ''Felvidék'' (literally: "Upland"), the Hungarian term for the area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now mostly present-day Slovakia. The region has also been ...

(present-day Western Slovakia

Western Slovakia ( sk, Západné Slovensko) is one of the four NUTS-2 Regions of Slovakia. It was created at the same time as were the Nitra, Trnava and Trenčín regions. Western Slovakia is the most populated of the four regions of Slovakia and ...

), within the 1848/49 revolution in the Habsburg Monarchy. It lasted from September 1848 to November 1849. During this period Slovak patriots established the Slovak National Council

The Slovak National Council ( sk, Slovenská národná rada (SNR)) was an organisation that was formed at various times in the 19th and 20th centuries to act as the highest representative of the Slovak nation. It originated in the mid-19th century ...

as their political representation and military units known as the Slovak Volunteer Corps.

The political, social and national requirements of the Slovak movement were declared in the document entitled "Demands of the Slovak Nation" from April 1848.

Serb Revolution of 1848–1849

The Serb Revolution of 1848 was an uprising of Serbs living inDélvidék

''Délvidék'' (, "southern land" or "southern territories") is a historical political term referring to varying areas in the southern part of what was the Kingdom of Hungary. In present-day usage, it often refers to the Vojvodina region of Serbia. ...

against Magyar domination. The majority of the Serbs there sided with the Austrians. However, there were also some exceptions, e.g. General János Damjanich

János Damjanich ( sr, Јован Дамјанић, Jovan Damjanić; 8 December 18046 October 1849) was an Austrian military officer who became general of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army in 1848. He is considered a national hero in Hungary.

Ea ...

of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army

The Hungarian Defence Forces ( hu, Magyar Honvédség) is the national defence force of Hungary. Since 2007, the Hungarian Armed Forces is under a unified command structure. The Ministry of Defence maintains the political and civil control over ...

.

The Second Wave of Revolutions

Revolutionary movements of 1849 faced an additional challenge: to work together to defeat a common enemy. Previously, national identity allowed Habsburg forces to conquer revolutionary governments by playing them off one another. New democratic initiatives in Italy in the spring of 1848 led to a renewed conflict with Austrian forces in the provinces of Lombardy and Venetia. At the very first anniversary of the first barricades in Vienna, German and Czech democrats in Bohemia agreed to put mutual hostilities aside and work together on revolutionary planning. Hungarians faced the greatest challenge of overcoming the divisions of the previous year, as the fighting there had been the most bitter. Despite this, the Hungarian government hired a new commander and attempted to unite with Romanian democrat Avram Iancu, who was known as ''Crăişorul Munţilor'' ("The Prince of the Mountains"). However, division and mistrust were too severe. Three days after the start of hostilities in Italy,Charles Albert of Sardinia

Charles Albert (; 2 October 1798 – 28 July 1849) was the King of Sardinia from 27 April 1831 until 23 March 1849. His name is bound up with the first Italian constitution, the Albertine Statute, and with the First Italian War of Independence ...

abdicated the throne of Piedmont-Savoy, essentially ending the Piedmontese return to war. Renewed military conflicts cost the Empire the little that remained of its finances. Another challenge to Habsburg authority came from Germany and the question of either "big Germany" (united Germany led by Austria) or "little Germany" (united Germany led by Prussia). The Frankfurt National Assembly proposed a constitution with Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia as monarch of a united federal Germany composed of only 'German' lands. This would have led to the relationship between Austria and Hungary (as a 'non-German' area) being reduced to a personal union under the Habsburgs, rather than a united state, an unacceptable arrangement for both the Habsburgs and Austro-German liberals in Austria. In the end, Friedrich Wilhelm refused to accept the constitution written by the Assembly. Schwarzenberg dissolved the Hungarian Parliament in 1849, imposing his own constitution that conceded nothing to the liberal movement. Appointing Alexander Bach head of internal affairs, he oversaw the creation of the Bach system, which rooted out political dissent and contained liberals within Austria and quickly returned the status quo. After the deportation of Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, poli ...

, a nationalist Hungarian leader, Schwarzenberg faced uprisings by Hungarians. Playing on the long-standing Russian tradition of conservativism, he convinced tsar Nicholas I to send Russian forces in. The Russian army quickly destroyed the rebellion, forcing the Hungarians back under Austrian control. In less than three years, Schwarzenberg had returned stability and control to Austria. However, Schwarzenberg had a stroke in 1852, and his successors failed to uphold the control Schwarzenberg had so successfully maintained.

See also

*United Slovenia

United Slovenia ( sl, Zedinjena Slovenija or ) is the name originally given to an unrealized political programme of the Slovenes, Slovene national movement, formulated during the Spring of Nations in 1848. The programme demanded (a) unification o ...

* Anton Füster

References

Bibliography

* * ), authorlink1=Karl Marx, authorlink2=Freidrich Engels , url=http://marxists.org/archive/marx/works/cw/volume09/index.htm, archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050209051404/http://marxists.org/archive/marx/works/cw/volume09/index.htm , archive-date=2005-02-09 * Nobili, Johann. ''Hungary 1848: The Winter Campaign''. Edited and translated Christopher Pringle. Warwick, UK: Helion & Company Ltd., 2021. * *Further reading

*Robin Okey, ''The Habsburg Monarchy c. 1765–1918: From Enlightenment to Eclipse'', New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002 *Otto Wenkstern, ''History of the war in Hungary in 1848 and 1849'', London: J. W. Parker, 1859Digitized version

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Revolutions Of 1848 Austrian Empire . .Austrian Empire 19th century in Bohemia 1840s in Croatia 1848 in Hungary 1848 in Romania 19th century in Slovakia 19th-century revolutions Conflicts in 1849 Hungarian Revolution of 1848 Rebellions against the Austrian Empire

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

Ferdinand I of Austria

Rebellions in Czechia